This article was originally published in the Fall 2022 edition of the AIM Newspaper. Read the full paper or subscribe to the print edition for free.

The thoracolumbar junction (TLJ), a region of the body often ranging from T11-L2, is an intriguing region which can open us to deeper understandings of the channel system. The neuro-myo-fascial anatomy of this region will be our guide into this deeper understanding and this article will explain some anatomy that I have been exploring, along with Matt Callison, in our ongoing cadaver studies within the Sports Medicine Acupuncture Certification program, and which I bring into my lectures on the anatomy of the channel system.

Understanding the Thoracolumbar Junction’s Anatomy and Channels

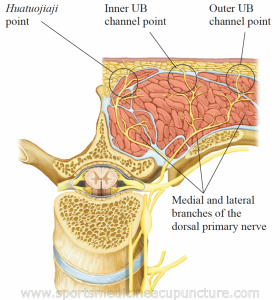

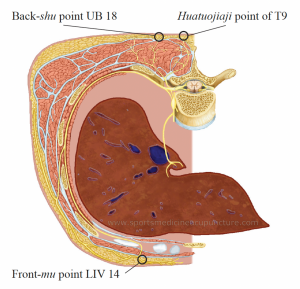

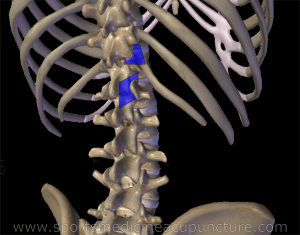

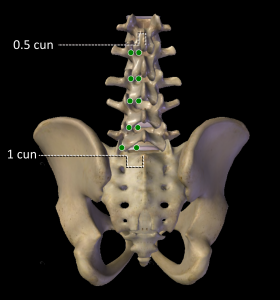

As with any region of the spine, there are spinal nerves which carry messages away from the spinal cord and bring messages back in. This information comes into and leaves the spine via the spinal nerve roots. The thoracolumbar junction, like all regions of the thorax and the upper lumbar region, has distinct branches, or rami, extending from these roots. There is a ventral ramus which supplies the skin and muscles of the anterior trunk. And there is a dorsal ramus which supplies the skin and muscles of the back. The first important neurological lesson that informs our discussion on the channels is that this dorsal ramus has two branches: a medial branch that travels up the lamina and is part of the huatuojiaji points, and a lateral branch that itself splits to contribute to the inner and outer bladder line. Both the medial and lateral branch supply skin and muscles in their respective regions, but there is a rich network of sensory receptors from the medial branch that also innervates the capsule of the facet joints (Bogduk, 1997). This is the farthest lateral reach of the huatuojiaji points.

Are you interested in becoming a certified acupuncture professional?

Visit the links below to explore our specialized acupuncture programs at a campus near you:

Another branch from the spinal nerve root supplies the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system. This travels to various ganglia and ultimately to visceral smooth muscles and glands to regulate the internal environment in our ventral cavity. There is nothing particularly different at the thoracolumbar junction region regarding this path, though it is worth noting that the nerves from the TLJ segments primarily innervate the midgut, the kidney organ, and the adrenal glands.

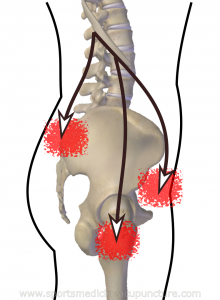

What is a bit unique at the TLJ is the nerves that branch from both the dorsal and the ventral rami. In addition to dorsal rami innervating the skin and muscles of the back in the region, muscles such as the iliocostalis lumborum, longissimus thoracic (inner and outer UB channel lines), and multifidi (huatuojiaji points), there is also a more extensive network of sensory nerves that travel posterior to the quadratus lumborum, pierce the thoracolumbar fascia just above the iliac crest, and then drape over the iliac crest to supply the skin in the gluteal region (Elsharkawy, 2019). These are the superior cluneal nerves.

Clinical Patterns and Diagnosis of Thoracolumbar Junction Syndrome

There is a very common clinical pattern that we see with patients called thoracolumbar junction syndrome (TLJS). This is an irritation of the neuro-myo-fascial segment that refers pain to the low back following the dorsal rami distribution over the iliac crest and in the region of the sacroiliac joint, and/or of the neuro-myo-fascial segment that refers pain to the greater trochanter region, inguinal region, or groin following the ventral ramus nerves (Zhou, 2012) (Kim, 2013).

So, what causes the irritation in the first place? In the literature, this syndrome is defined as a minor, intervertebral dysfunction at the TLJ (Mainge, 1980). It might even be described as a dysfunction of the facet joints of this region, but this condition rarely presents with any significant degenerative changes at these levels (Mainge, 1980) (Aktas, 2014). The condition is mostly attributed to the change of movement that occurs at the TLJ. The thoracic facets have an orientation that allows for a rotation that is especially active at T11 and 12, since there are floating ribs here and the ribcage does not limit the rotation. The lumbar facets, on the other hand, have an orientation that does not permit very much rotation. Because of this crossroads of movement, this area is susceptible to becoming hypomobile; the facets become irritated and this irritation is transmitted along the ventral or dorsal pathways to cause pain along these pathways and stiffening in the muscles innervated along the way. The pain is far enough from the source that it is not surprising that this syndrome is frequently missed by clinicians.

Linking TLJS with Western and Chinese Medicine Perspectives

TLJS is inconsistently described in the literature in reference to the viscera. For instance, sometimes it is described as having a visceral component, understood to present with conditions such as IBS. I have seen clinicians publish cases where pain persisted with conditions such as renal artery stenosis even after insertion of a renal stent, for instance, and the pain was diagnosed eventually as TLJS (Noh K, et al 2020). At other times it is described as having a pseudo-visceral component, presenting with gynecological, urologic, testicular, and lower GI pain not of visceral origin (Mainge, 1980) (Aktas, 2014). As an acupuncturist, I don’t know that I see those as two completely different things, especially if you consider it from a Chinese medical perspective; but honestly, even a standard neurological perspective illustrates how integrated this anatomy is. I feel that this entire neurological segment becomes irritated whether the problems began in the organs or the channels.

Pain from TLJS is assessed by mobilizing and applying pressure to the associated facet joints of the TLJ, checking if this recreates or aggravates the pain. In addition, it is important to note the pain distribution, as this will help indicate whether the dorsal or ventral pathway is affected. Sometimes, due to the pain following the dorsal nerve distribution, the condition is referred to in the literature as posterior rami syndrome and the pain can follow the medial and/or the lateral dorsal ramus distribution (Zhou 2012). If the pain is described as midline and reaching to the boundary of the huatuojiaji points or sacroiliac joint, then the medial branch is involved, whereas the lateral branch will be felt lateral to the huatuojiaji points. Anatomically, the facets are the dividing line. If the common dorsal ramus is affected, the pain will be in both regions.

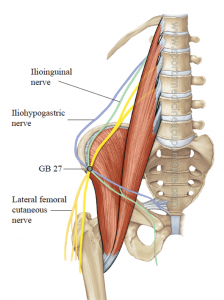

With other patients, the pain refers in front and wraps around the waist to the groin following the nerves from the ventral rami. Patients feel this pain in the greater trochanter region, the inguinal region, and/or the groin, indicating this distribution.

Myofascial trigger points are usually not mentioned when you read discussions of TLJS, but the parallels are so obvious that it makes sense to consider them. The muscles innervated by these dorsal or ventral distributions of nerves will also become irritated, contributing to the stiffness at this segment, but also referring pain in the same regions. These muscles can therefore be palpated to see if there is pain and referral from trigger point formation. If you look up the trigger points for muscles innervated by the dorsal ramus (multifidi, iliocostalis lumborum, and longissimus thoracic and portions of the QL that I believe are likely the medial fibers which attach to the spine), you will see that their pain referrals are the same as that described in TLJS for the sensory nerve distribution of the dorsal ramus. If you look at the trigger point referrals for the muscle innervated by the ventral ramus of the TLJ (QL, psoas, lower abdominals), you will see that these parallel the subcostal, ilioinguinal, and iliohypogastric nerves. Understanding this relationship allows us to expand the treatment beyond just a mobilization of the TLJ facets which is a typically recommended treatment for this condition. A knowledge of what channel sinews (jingjin) these muscles belong to elevates the treatment options even more, as we can link effective distal points with the local treatment. A full Chinese medicine assessment will link the condition to any organ disharmony, further expanding the treatment options for the patient.

I will be presenting on this topic at the Pacific Symposium this year and we will take the time to explore how to assess and treat this condition with acupuncture, manual therapy and corrective exercises. It is a common condition, and it is very worth learning how to help patients presenting with TLJS. We benefit from understanding Western anatomy, and this will bring to life our understanding of the channel system.

References:

- Aktas I, Akgun K, Kenan & Palamar D, Saridogan M. Thoracolumbar Junction Syndrome: An overlooked diagnosis in an elderly patient. Thurk Geriatri Dergisi. 2014;17.

- Bogduk N. Clinical Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine and Sacrum. Ed 3. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1997. Low back pain; pp. 187–214.

- Callison, M., Schreiber, A., T., R. V. N., Livermore, M., & Scoggins, A. (2019). Sports medicine acupuncture: An integrated approach combining sports medicine and traditional Chinese medicine. AcuSport Education.

- Elsharkawy, H., El-Boghdadly, K. and Barrington, M., 2019. Quadratus Lumborum Block. Anesthesiology, 130(2), pp.322-335.

- Kim SR, Lee MJ, Lee SJ, Suh YS, Kim DH, Hong JH. Thoracolumbar Junction Syndrome Causing Pain around Posterior Iliac Crest: A Case Report. Korean J Fam Med. 2013 Mar;34(2):152-5. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.2013.34.2.152. Epub 2013 Mar 20. PMID: 23560215; PMCID: PMC3611104.

- Zhou, C. Schneck and Z. Shao, “The Anatomy of Dorsal Ramus Nerves and Its Implications in Lower Back Pain,” Neuroscience and Medicine, Vol. 3 No. 2, 2012, pp. 192-201. doi: 10.4236/nm.2012.32025.

- Maigne R. Pain syndromes of the thoracolumbar junction: A frequent source of misdiagnosis. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics. 1980;8(1):87-100

- Noh K, Jung JB, Seong JW, Kim DE, Kwon D, Kim Y. Thoracolumbar Junction Syndrome Accompanying Renal Artery Stenosis: A Case Report. Ann Rehabil Med. 2020;44(1):85-89. doi:10.5535/arm.2020.44.1.85

Featured Posts: