Using the Gluteus Medius, the Quadratus Lumborum, and the Sacral-Iliac Joint in the Treatment of Low Back and Hip Pain

This article was originally published in the Winter 2023 edition of the AIM Newspaper. Read the full paper for free.

Introduction

After years of experience, I have come to understand that there is nothing more complex to differentiate, diagnose, and treat than low back pain. Western orthopedic evaluation does a reasonable job when there is a disc herniation with an extruded fragment compressing a spinal nerve root. Anything else, in my opinion, is either art or guesswork. I have seen many patients who have been to physicians, each diagnosing a different cause of pain, and of course many had been subjected to numerous unsuccessful procedures.

Unfortunately, Chinese medical diagnosis is not always precise, and often does not offer a path to successful clinical results. I gave up on treatment based upon the meridian (jingluo) perspective several decades ago when taiyang points such as Bladder 23, Bladder 25, Bladder 40, and Bladder 60 failed to produce adequate pain relief. From the internal organ (zangfu) perspective, treating the kidney, which “controls the lumbus” in traditional Chinese theory, has also proven to offer unreliable protocols. And even the simple technique of treating prominent ahshi points has also failed to impress with good lasting clinical results.

In the end, as a clinician, I accept that it is never as simple as a disc protrusion being the single cause of back and leg pain. The practitioner needs to look deeper into the anatomical structures and postural muscles that generate pain. It is only then that our treatments and choice of points target the primary sites of qi and blood stagnation. It may feel like we are stripping the metaphoric language of Chinese medicine, such as shen, the emotions, and organ physiology, but this may be the most expedient way to arrive at a diagnosis fit for a modern clinical patient.

“The Triad” of Low Back Pain

Based on my four decades of clinical observation and treatment, you can count on the triad to be involved with most patients complaining of back pain. Whether it be trigger points, tendonitis and muscle strain, joint inflammation, or tight, shortened and contracted postural muscles, the triad generates pain and perpetuates dysfunction in this mid-section of the body. And to further confuse the case, these structures produce “referred” pain, which can frustrate the unsuspecting practitioner.

For the purposes of this article, we will focus on the triad’s role in low back pain. While these structures may not be the entire cause of pain—other points, treatments, and techniques may be necessary—the simple techniques that follow may assist in choice of points and may serve as an important protocol for acupuncture treatment.

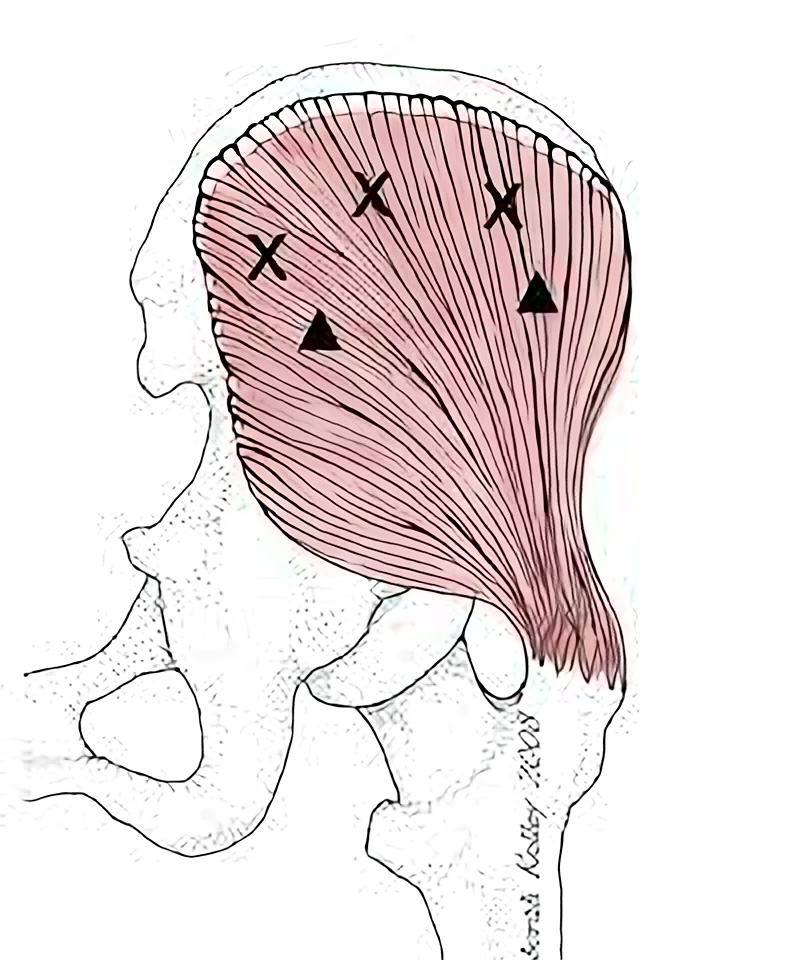

The Gluteus Medius

The gluteus medius is an important abductor; it lifts the leg to the side when standing or side lying. However, perhaps more importantly, it prevents the pelvis from tilting or dropping when single leg standing. Diagnostically, this is called the Trendelenberg posture or gait. It is simple: when the muscle is weak or inhibited, the pelvis drops on the opposite side of the weight bearing leg. This finding may often be overlooked by the practitioner, and thus treatment to the gluteus medius may be missed.

It is important to note that single-leg standing occurs while both walking and running—with every step that we take! This is how we move from heel-strike to toe-off in all lower extremity movement. If the Trendelenberg is positive—if the pelvis drops even slightly—this becomes a significant biomechanical issue. That means that, with each step, the pelvis and lumbar spine are subjected to repetitive stress. Long term, this is not advantageous to optimal spine and hip joint health. The importance of this function of the gluteus medius cannot be overstated.

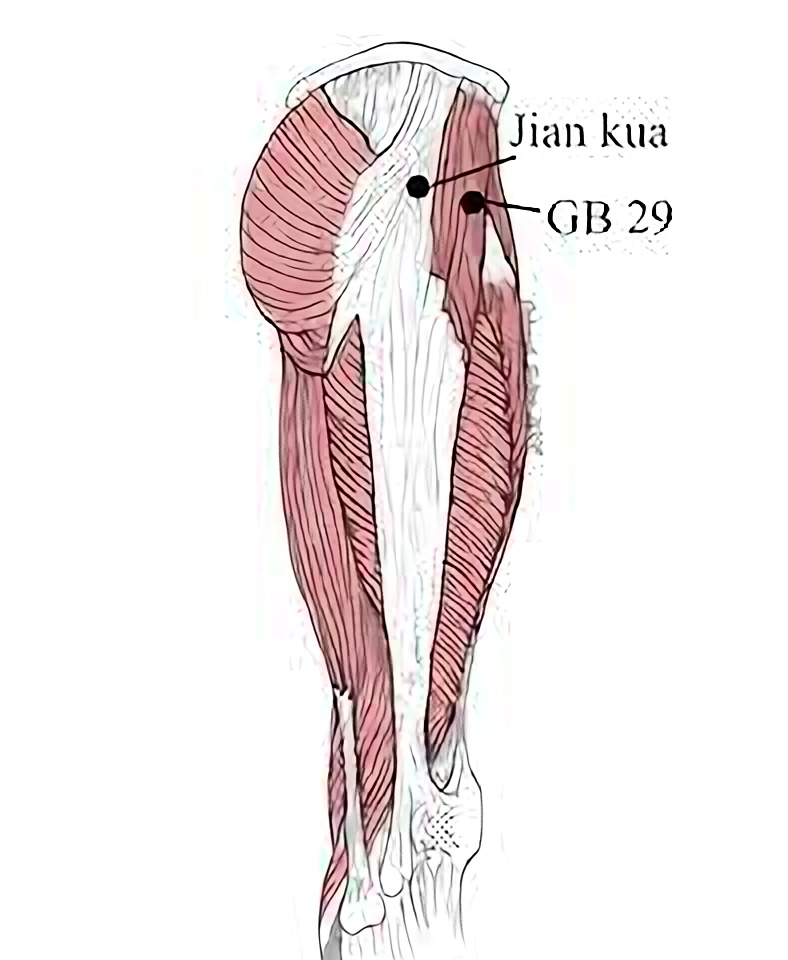

Fortunately, it is easy to spot during assessment. Manual muscle testing will usually reveal that the gluteus medius is weak due to inhibition. This is because it is a phasic muscle, which tends toward being inhibited or “turned off” when there is trauma or stress. Prolonged sitting at a desk or while driving can induce this stress. Therefore, it is advised that the practitioner learn how to test for resisted leg abduction, the primary action of the gluteus medius, in order to confirm this finding. Additionally, palpate the muscle belly of the gluteus medius at the extraordinary point Jiankua N-LE-55.[i] We’ll discuss this below in more detail, but a stressed or inhibited muscle will be revealed with ahshi. Once identified, the glute med obviously needs to be treated!

The extraordinary point Jiankua N-LE-55

Jiankua is not a traditional acupuncture point, nor is it a commonly known extraordinary point; yet it lies in the muscle belly of the gluteus medius, which in physical therapy and exercise physiology is one of the most important muscles in treating and rehabbing the low back. Most practitioners have found this zone to be a significant ahshi point at one time or another while palpating the hip. Hopefully, you will be able to locate this point with precision and use it with confidence. Don’t be distracted by the many other potential painful points during palpation. Jiankua will usually be found precisely at the location above and will likely become one of the most important points you will use in the treatment of low back pain.

Let us continue. In addition to this important role of stabilizing the pelvis and lumbar spine, the gluteus medius produces numerous referral pain patterns to the lumbo-sacral region. So pervasive is this pain pattern that Janet Travell, MD, in her text Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction, calls the gluteus medius the “lumbago” muscle. It refers pain to the lumbo-sacral, gluteal, and hip regions of both the taiyang and shaoyang zones. Trust me, this can be confusing to the practitioner who is not alerted to these common pain patterns.

The deeper gluteus minimus must also be mentioned. It also has its own pain referral patterns, which Dr. Travell describes as the “pseudo-sciatica” muscle. The defined pain pattern is down the lateral or posterior thigh.[ii]

Let’s make it simple. Both of these layered muscles are usually overlooked in a Chinese-style jing-luo treatment perspective. Assume that the gluteus medius and gluteus minimus are involved in virtually all cases of low back and hip pain. As such, treatment in the zone of Jiankua will be an effective tool in the point prescription.

Are you interested in becoming a certified acupuncture professional?

Visit the links below to explore our specialized acupuncture programs at a campus near you:

Jiankua is treated with 2- to 3-inch (50mm to 75mm) needles, depending on patient size. It is best needled perpendicularly. Deep needling is necessary, and with care, insertion is generally comfortable for the patient. The needle will penetrate both the gluteus medius and, deeper, the gluteus minimus. Prone (face-down) or side lying (lateral recumbent) are the most common positions. I frequently use two paired points in the muscle belly at the zone of Jiankua. Electrical stimulation between these two paired points often provides significant relief for a variety of the local and referred symptoms.

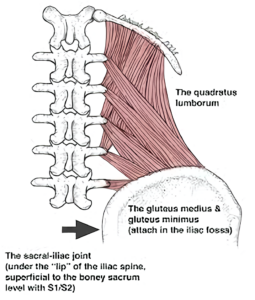

The Quadratus Lumborum (The QL)

Janet Travell calls this muscle the “joker of low back pain”.[v] It has a varied referral pattern, but much of the problem is that it anatomically lies deep to the superficial muscles of the erector group of the lumbar spine. Therefore, it may be missed by palpation as well as needling. However, the practitioner must address this muscle in order to succeed in the treatment of low back pain, whether acute or chronic.

Let’s say this again, in stronger language. The practitioner will have only modest success in the treatment of low back pain without proper assessment and precise treatment of the quadratus lumborum muscle.

So important yet elusive, no common acupuncture points are found on this important muscle of the low back. All of this may demand some adaptability and flexibility of the practitioner, as it is a contrarian view to what is found in many common professional practices, but the QL will become an ally of the dedicated practitioner!

Treatment of the QL

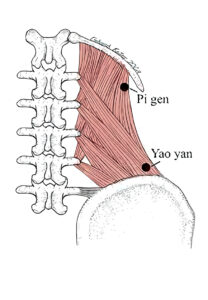

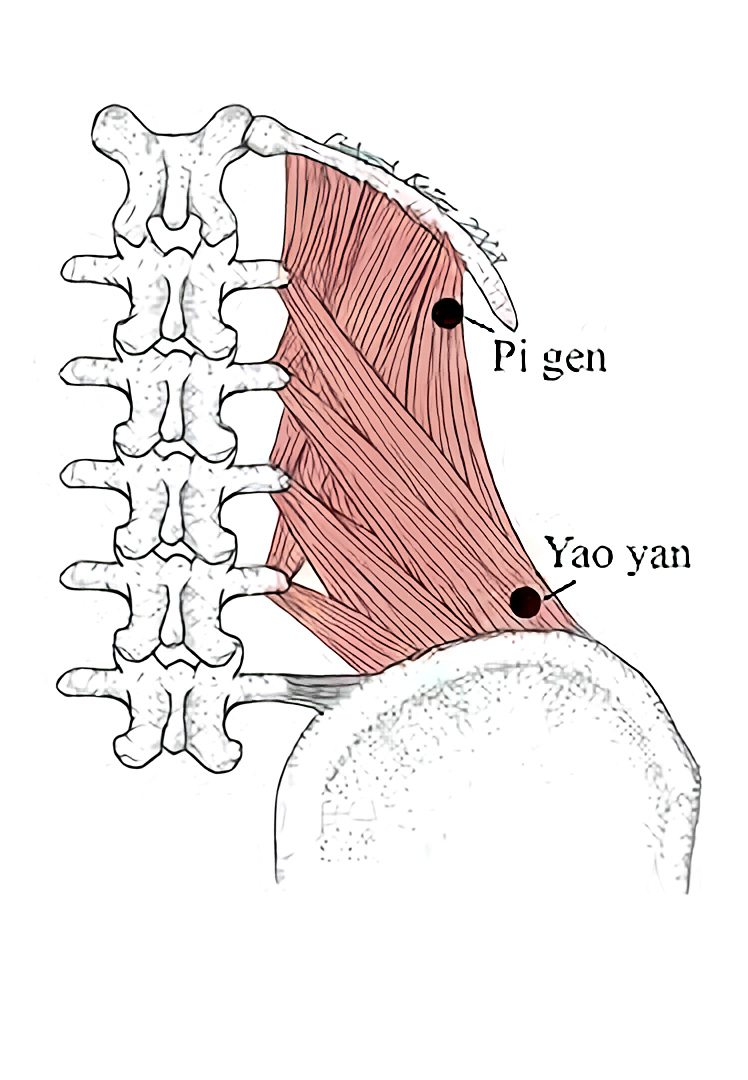

The extraordinary point Pigen is the place to start. It is at or near one of the important trigger points of the QL, and is frequently an ahshi point. The texts locate Pigen 3.5 cun lateral to the spinous process of the first lumbar vertebrae. Don’t be concerned if it is located slightly inferior or further lateral than 3.5 cun, as there are some variations with this empirical point. Palpation is the key to both its location and successful needling.

With the patient prone or lateral recumbent, start palpating about 4 cun lateral to the spine, approximately level with L1, and immediately inferior to the 12th rib. You should be just off the border of the para-spinal muscles and slightly lateral to the outer bladder meridian. Palpate medially towards the vertebral column until the painful point or zone is found. You are palpating deep to the para-spinal muscles, which is actually anterior to this muscle group. The patient will often exclaim “that’s the spot!” when you reach that perfect location and precise angle. The more common perpendicular palpation along the para-spinal muscles and the course of the bladder meridian will usually not reveal this ahshi point.

There are other points along the band of the QL inferior Pigen to explore. The practitioner should continue to palpate down (inferior) along the muscle belly of the quadratus lumborum. Often, a second point can be found about 1 cun inferior to Pigen. This is in the region of one of the motor points of the QL, located level with L2, from .5 to 1 cun lateral to bladder 52.[vi] There is often also an ahshi point at the inferior attachment of the QL, just superior to the iliac crest. This is the region of the extraordinary point Yaoyan, described in the texts as 3.5 cun lateral to the lower border of the spinous process of L4. Keep in mind that the point is just superior to the iliac crest, which is not how it is pictured in the text A Manual of Acupuncture.[vii] For the purpose of low back pain treatment, superior to the crest of the ilium, in the attaching fibers of the QL, is the location of choice.

Needle technique

Either position, prone or lateral recumbent, is acceptable for needling. However, it is important to insert the needle with the same vector that produced the pain during palpation. Patient size will determine the length to be used, which is usually 2 to 3 inches (50mm to 75mm). After insertion, direct the needle oblique to transverse toward the vertebral body, deep to the para-spinal muscles, until the taut and dense tissue of the QL is reached. Review the anatomy and, if need be, get help from an experienced practitioner. It is important to avoid deeper insertion into the kidney, the peritoneum, or the pleural cavity. So proceed with caution!

One or some combination of several of the ahshi points between Pigen and Yaoyan is usually successful in relieving pain and spasm of the muscle. I frequently use the two most significant ahshi points along the muscle belly as described. Consider electrical stimulation between two paired points, remembering that some patients do not tolerate strong stimulation.

It is not uncommon to complete the needle treatment of the QL with cupping. Manual therapy and variations of tui na are also indicated and often welcomed by the patient. If the case is relieved with heat, indirect moxa or thread moxa may be applied as well as other applications of moist heat.

The Sacral-Iliac Joint (SI joint)

With the quadratus lumborum superior, and the gluteus medius and minimus inferior, the triad is completed with the sacral-iliac joint. The SI joint is a synovial hinge joint, and is frequently missed in both Western and Chinese medical diagnosis. The reader may have never read references to treating the SI joint dysfunction in any of the common treatment formularies of Chinese acupuncture. Its absence does not, however, mean one should not include it in assessment and treatment in the modern clinic.

The posterior sacral-iliac ligaments “strap” the region of the sacrum and ilium, and are responsible for much of the stability of the SI joint. Thus the more superficial needle penetrates these ligamentous structures. Deep to the ligamentous zone lies the synovial joint, and any needle with deeper insertion may affect these articular tissues. Even after one acupuncture treatment, many patients may feel more “stability” in the joint due to the invigoration of qi and blood at the ligaments and joint capsule. The addition of electrical stimulation will also address inflammation and stagnation in the joint. In cases of cold bi syndrome, needle top moxa can be considered.

The anatomical access zone of the sacral-iliac joint is in the region of bladder 27 and bladder 28. On the lateral aspect of the sacrum lateral to the first and second sacral foramen, the practitioner should palpate with a 45-degree oblique lateral angle. Again, to repeat, 45-degree oblique lateral palpation! Or if one prefers, follow the crest of the ilium posteriorly, to the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS). Using the high point of the PSIS, palpate medial and inferior to the access zone of the SI joint. A 45-degree oblique lateral angle will slide along the lateral sacrum while remaining under the lip of the ilium and the PSIS. That is the perfect zone for the sacral-iliac ligaments as well as the joint itself.

There are numerous orthopedic tests to confirm the SI joint. I rely on the symptoms of the patient, which usually are reported to be deep local pain in the sacral region described above, and digital palpation, which has been extremely reliable in assessing dysfunction of the SI joint. If it is ahshi, consider that the third structure of the triad, the sacral-iliac joint, is involved and should be included in the treatment.

Needle technique

Needling the SI joint follows logically from palpation. Medial and inferior to the PSIS, on the sacrum, at or slightly lateral to bladder 27 and bladder 28, needle 45 degrees oblique lateral. A 2- to 3-inch (50mm to 75mm) needle is sufficient in most cases, and don’t be disheartened if the needle fails to penetrate the joint. This is not always easy, although either prone or lateral recumbent usually offers a position that is successful for the necessary deep needle insertion; like the gluteus medius and the QL, electrical stimulation may benefit.

Treating the Triad as a Whole

When a case presents with all structures of the triad being involved, needling these three anatomical zones together is advantageous. Lateral recumbent is my preferred position, with a pillow between the knees. However, prone (face down) is also acceptable. The quadratus lumborum and the gluteus medius are easy to access, and needling in either of these two positions is effective. The sacral-iliac joint may be a bit more complicated, as it is usually successful in only one of the positions. If side lying does not produce the ahshi confirmation for the SI joint, the patient may need to be prone for best results.

To repeat, lateral recumbent is the most likely position for treating the triad structures. However, with a stubborn sacral-iliac joint requiring prone position, you may need to treat in two phases. Lateral recumbent for the first 15 minutes and prone for the next 15 minutes. Of course, you can vary the phases, making them slightly more or slightly less than the suggested 15 minute time. With this two-phase system, all three structures get adequate needling.

Final Remarks

Acupuncturists are always looking to refine their treatment protocols for treating low back pain. The triad—the gluteus medius and minimus, the quadratus lumborum, and the SI joint—might not always be the primary cause, but they often have significant contribution to the case. This treatment protocol may be overlooked by the acupuncturist due to its more complex anatomical description as well as the lack of well-known points. However, in the end, the triad may serve as the foundation for treatment of low back pain, regardless of the actual cause or causes. Whether for bulging discs, sprain and strain to the vertebral column, facet joint syndrome, or other such disorders of the lumbar spine, I am sure you will find the triad surprisingly effective.

Important Clinical Note

The practitioner should understand the shortcomings of an article as the sole guide in the treatment of these structures of the low back. The kidney, the lung, and the peritoneal cavity lie deep to some of the acupuncture points used for back pain. The intention is to initiate a discussion and provide an anatomical foundation for understanding the deeper causes of low back pain. It may require more instruction to master the location and needling of the acupuncture treatments presented.

References

The Acupuncture Handbook of Sports Injuries and Pain (Hidden Needle Press, 2009), by Whitfield Reaves, with contribution from Chad Bong. Illustrations by Deborah Kelley.

[i] Shanghai College of Traditional Medicine: Acupuncture, A Comprehensive Text. Eastland Press, Chicago, 1981 (page 378).

[ii] Travell & Simons: Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual, Volume 2 (The Lower Extremities). Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 1992 (page 150, page 168).

[iii] Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion, Foreign Language Press, Beijing, China, 1993 (page 236).

[iv] Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion, Foreign Language Press, Beijing, China, 1993 (pages 236-237).

[v] Travell & Simons: Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual, Volume 2 (The Lower Extremities). Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 1992 (pages 28-32).

[vi] Matt Callison, MS, LAc, Motor Point Index, AcuSportSeminar Series, San Diego, CA, 2007 (page 94).

[vii] Deadman et al, A Manual of Acupuncture, Journal of Chinese Medicine Publications, 1998 (page 572).

Featured Posts: