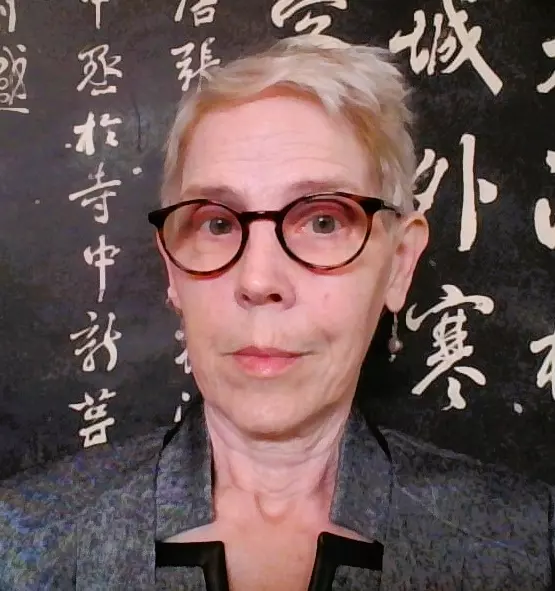

By Lorraine Wilcox, LAc, PhD

This article was originally published in the Fall 2022 edition of the AIM Newspaper. Read the full paper or subscribe to the print edition for free.

I am fascinated with the material culture of Chinese medicine. I want to know how they did things. I want to watch a Ming dynasty doctor manipulate the needle. I want to observe while an imperial physician reads the pulse and writes out a formula. I want to see the tools of ancient pharmacies and the way they were used. I especially want to know how they prepared their prescriptions, step by step. Ever since I began teaching myself to read Chinese, I have tried to understand the instructions, not just the ingredients of ancient remedies. I started by replicating the methods of moxibustion I found in ancient texts. I often burned myself, so I practiced and improved my skills. Later I focused on making different types of herbal medicine in my kitchen: decoctions, pills, powders, syrups, ointments, plasters, even medicinal incense and medicinal snuff.

In modern times, many people have reduced the practice of herbal medicine to granules and manufactured pills. This is certainly time-saving and convenient for patients. In many or most cases, this is probably adequate. Decoctions are also still common. But I hope we do not lose the knowledge of pill-making, powders (meaning ground-up herbs), or syrups. For myself, I have found homemade formulations more effective than any store-bought pill.

If you think a career in holistic medicine is something you would like to pursue, contact us and speak to an admissions representative to get started on your new journey!

Step-by-Step Guide to Making Traditional Honey Pills

Here is a short tutorial on the basic method for making honey pills, such as Shenqi Wan (Kidney Qi Pill) or Liuwei Dihuang Wan (Six-Ingredient Pill with Rehmannia). Don’t be discouraged if your first attempt is not perfect. It took me a few tries too.

Preparing Herbal Ingredients and Processing Honey

Step 1: Measure out the ingredients (whole herbs) and grind them into fine powder. This means grinding with an ‘electric grain mill’ or something similar and sifting with a ‘100-mesh’ sieve. If the herbs are not ground finely enough, the mouth-texture is unpleasant.

- If sticky herbs like shudihuang (Rehmannia Radix praeparata) are in the formula, bake them until they are dry and brittle, then measure out the weight. Grind the other herbs first, then add in small pieces of the sticky herb and grind again.

- If there are resins like ruxiang (frankincense), it is better to buy them pre-powdered. Otherwise, they will gum up your grinder.

Alternately, you could have your pharmacy grind the whole pill formula for you. Granules alone cannot be made into honey pills as they are designed to dissolve; they cannot properly thicken the honey to make pills that maintains their shape.

Step 2: Process the honey. Simmer honey on low heat to evaporate some of the water content. Before you bemoan the loss of enzymes, I remind you that ancient people did not use honey because of the enzymes. This is the traditional way of pill-making. When the water content is reduced, pills are less sticky and can be preserved for longer. You can make pills with unprocessed honey, but they will be stickier – they are more likely to adhere to each other and get stuck in your teeth like peanut butter.

Forming the Honey Pill Dough

Step 3: While the honey is still hot, drizzle a little onto the powder and work it in–but first, reserve a bit of powder in case you add too much honey. You can also use the reserved powder to keep the dough from sticking to your hands or the mortar and pestle. The goal is to use a minimum of honey with the powder. Keep drizzling in more honey and working it in until the dough looks a bit dry but holds together when packed into a ball. The dough may look too dry now, but once it is pestled, the texture will change.

Step 4: Put the dough in a mortar. Pestle it a hundred times or more. The texture will become smooth and moist, but not sticky. If it is still sticky, pestle in more powder. If it is too dry, the dough won’t hold together or will tend to crack apart. In that case, work in a small amount of honey. You may need to pestle it in batches if your mortar is too small. Alternately, you can knead it a hundred times, like bread dough.

Do Steps 3 and 4 while the honey is still quite warm; otherwise, the honey can harden and be difficult to work with. Be careful not to burn yourself.

Shaping and Storing the Pills

Step 5: Roll pills the size of large grapes. You can simply break off pieces and roll the pills. I roll out strips, cut them into pieces, and then roll each piece. If the pills are sticky, you can roll them in the powder to coat the outside. Some people coat the pills by rolling them in a pan that contains a thin layer of oil.

Step 6: Store the pills in an airtight container and keep in a cool dry place.

Traditional Honey Pill Recipes and Their Benefits

Honey pills are chewed before swallowing. The dose and frequency depend on the formula. They have a long shelf life since honey is a preservative. Usually, the worst that will happen is that they become dry and hard as they age. Here is an easy recipe for a great-tasting honey pill:

Sangma Wan (Mulberry Leaf and Sesame Seed Pill) Recipe

80 grams of sangye (Mori Folium) powder

40 grams of black sesame seed powder

honey

Powder and sift the above dry ingredients. (Black sesame seed powder can be bought in many Asian food stores. Mulberry leaves are easy to powder in a spice grinder but be sure to sift with a 100-mesh sieve, so the powder is flour-like.)

Process the honey and make pills as described above. You can roll the pills in the sesame powder to make the outside less sticky. Pills should be about 9 grams each (but I never measure). Take one in the morning and evening.

Sangma Wan enriches liver and kidney yin, benefits the head and eyes, blackens the hair, nourishes blood, and moistens dryness.

Featured Posts: