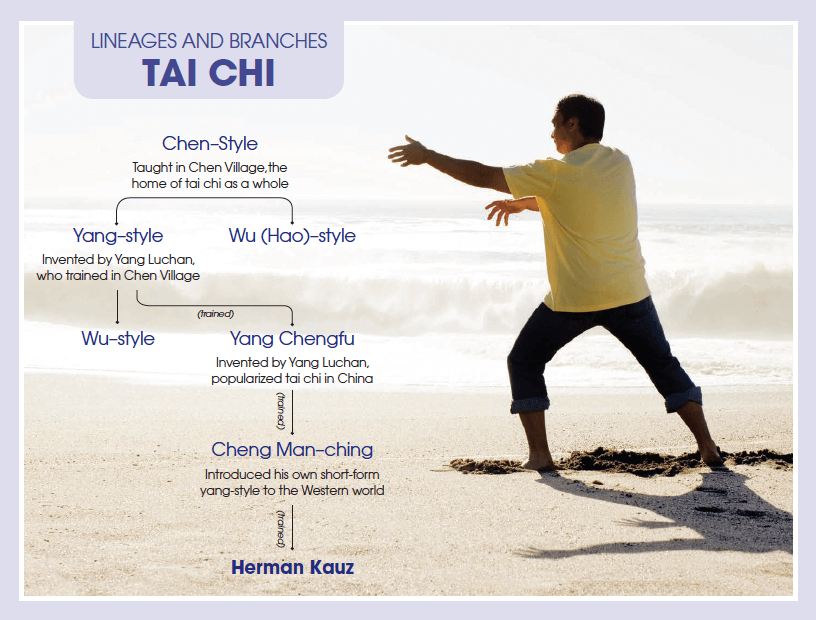

Herman Kauz has been a prominent teacher of tai chi for over 60 years. For the past 15 years, he has instructed the free Push-Hands class on the San Diego campus. In the 1970s, he trained with Cheng Man-ching, himself a student of Yang Chengfu, who was one of the most famous teachers of tai chi ever to have lived. Cheng Man-ching’s short-form Yang-style tai chi, one of the first to be introduced to the West, has since become the most widespread style of the art in the Unites States. He is the author of several well-regarded books in the field, including The Martial Spirit, A Path to Liberation, Push-Hands: The Handbook for Non-Competitive Tai Chi Practice with a Partner, and The Tai Chi Handbook.

How did you start on the path to tai chi?

At first, I studied judo in Hawaii in 1948, while I was in the Navy. I won the 1953 and 1954 champion heavyweight judo tournaments. Shortly afterward I was injured, then ended up taking karate after I had recuperated. I eventually traveled to Japan to learn more karate.

“Herman Kauz is part of the living tradition of martial arts in this county. He was the first to write a book on Cheng Man-ching’s Yang-style tai chi, and he has developed push-hands to a very high level using relaxation techniques.”

-Bill Helm, PCOM Faculty Member, Massage Department Chair, and Director of the Taoist Sanctuary of San Diego

So how did you end up switching from the harder martial arts, like karate and judo, to a soft art like tai chi?

I was looking for something more meditative. Both judo and karate could be thought to have that element in their approach, but I was reading about Zen and decided to go to Japan to study. I discovered, though, that I didn’t really like just sitting. I found it difficult to change from such an action-oriented approach, so I returned to New York and found Cheng Man-ching.

I’d previously studied with Stanley Israel (ed: considered to be one of, if not the best of the 1960s American judo practitioners, who pursued tai chi almost exclusively after meeting Man-ching), and Stanley recommended Cheng Man-ching. Some of my Hawaii friends had also studied with him.

I’d previously studied with Stanley Israel (ed: considered to be one of, if not the best of the 1960s American judo practitioners, who pursued tai chi almost exclusively after meeting Man-ching), and Stanley recommended Cheng Man-ching. Some of my Hawaii friends had also studied with him.

Man-ching needed enough money to support his family, so the people of Chinatown permitted him to teach outsiders, which at the time was extremely unusual. I was just after the first wave of people to learn from Man-ching. Originally, the beatniks that were part of the first wave were just looking for a “sage”, and Cheng Man-ching with his wispy beard, and as the Master of Five Excellences—those being painting, calligraphy, poetry, tai chi, and Chinese medicine—fit the type. The beatniks stuck around for push-hands once they found out about it, even though the Americans were so low-level they couldn’t really begin to touch Cheng Man-ching.

Tai chi grew on me and I stuck with it.

When did you start teaching martial arts?

When I first started teaching, I had more than 20 years of martial arts experience, but it was still too early. Tai chi is about learning to be in the moment, which I’m still developing even now. You need to suspend your thinking to avoid stopping the action. Everything must be spontaneous. Push-hands is the meditative process needed to develop the sense of what your opponent is about to do; you need that sense to trigger a precise reaction without involving your mind. That’s why it’s helpful for learning acupuncture; it’s about sensing and feeling the idea of qi.

Have you read The Power of Now, by Eckhart Tolle? You should. It’s sort of the same idea about being in the moment. For example: watching your breath; putting your attention on that creates space between thoughts and your thinking. In mindfulness, you’re watching your breath, and when a thought comes out you let it go; you don’t want to entertain these thoughts, but it’s very difficult since we’re not used to operating in this way.

When is a man in mere understanding? I answer, “When a man sees one thing separated from another.” And when is a man above mere understanding? That I can tell you: “When a man sees All in all, then a man stands beyond mere understanding.”

-Eckhart Tolle

How do you know if you’re doing tai chi correctly?

You need a teacher and you need people to practice with to know if you’re doing it correctly. You need to see if the opponent is ahead of you. The experienced person will see them coming and attack in response. Without thought, your body moves to get out of the way; your body becomes sort of like a ball that rotates in any direction it’s pushed, and moves to counter your opponent.

And if your opponent is better than you?

You’ll see soon enough if your opponent is ahead of you, as he knocks you off balance or opens you up to a strike.

How does push-hands fit into tai chi as a whole?

Through meditation, push-hands gives you the ability to respond automatically. We move slowly so that you can learn, but you must move to match your opponent; your speed is linked to your opponent’s speed. If they move faster you must move faster as well, and if you don’t sense their intention in time it’s too late.

What I teach is yang-style tai chi, but there are other takes. There is chen-style, which is stronger, with no idea of resisting, and wu-style, which is even softer than yang. Early on, chen seems like self defense–throwing people off balance, headlocks, that sort of thing.

What are the benefits of tai chi?

There are some cardiovascular benefits, but they’re limited. Mentally, though, you learn how to relax, and how to let go, which is very valuable. It takes time to develop. Some people come looking for self defense, and chen-style will help them go that direction very rapidly. You’ll get many more students if you have people that come by looking to be students, and you can throw them around or something like that, if that’s what you’re looking for. Our culture finds that to be desirable.

Through tai chi training, I believe students can derive perhaps 90 percent of the benefits martial arts can confer, with far fewer injuries. I teach Cheng Man-ching’s tai chi form and a rather tame, by fighting standards, push-hands in which foot positions are fixed and opponents use the very minimum of strength to off-balance or uproot one another.

–A Path to Liberation: a Spiritual and Philosophical Approach to the Martial Arts. Kauz, 1992.

When I started teaching here in San Diego in 2000, the class was initially counter to what I was looking for; it was proposed that we do contests. I can’t see this at all. It’s no good to have a competitive aspect, though it’s difficult to keep it out altogether, but the less you encourage competition between people, the better.

You can’t really say what tai chi is, you know; it has to be experienced. The thought, the word, is not really the thing. Not everybody agrees with what I have to say, but as I live longer and longer, people can’t contradict me so easily.

That’s a joke.

If you think a career in holistic medicine is something you would like to pursue, contact us and speak to an admissions representative to get started on your new journey!

Featured Posts: